Written by: Jhesset O. Enano, Matthew Reysio-Cruz, Philippine Daily Inquirer

(First of three parts)

MANILA, Philippines — Every morning, Roneldo Papong heads to a spartan hut on the edge of Marikina River, where he spends the hours keeping watch over the waters that once nearly killed him.

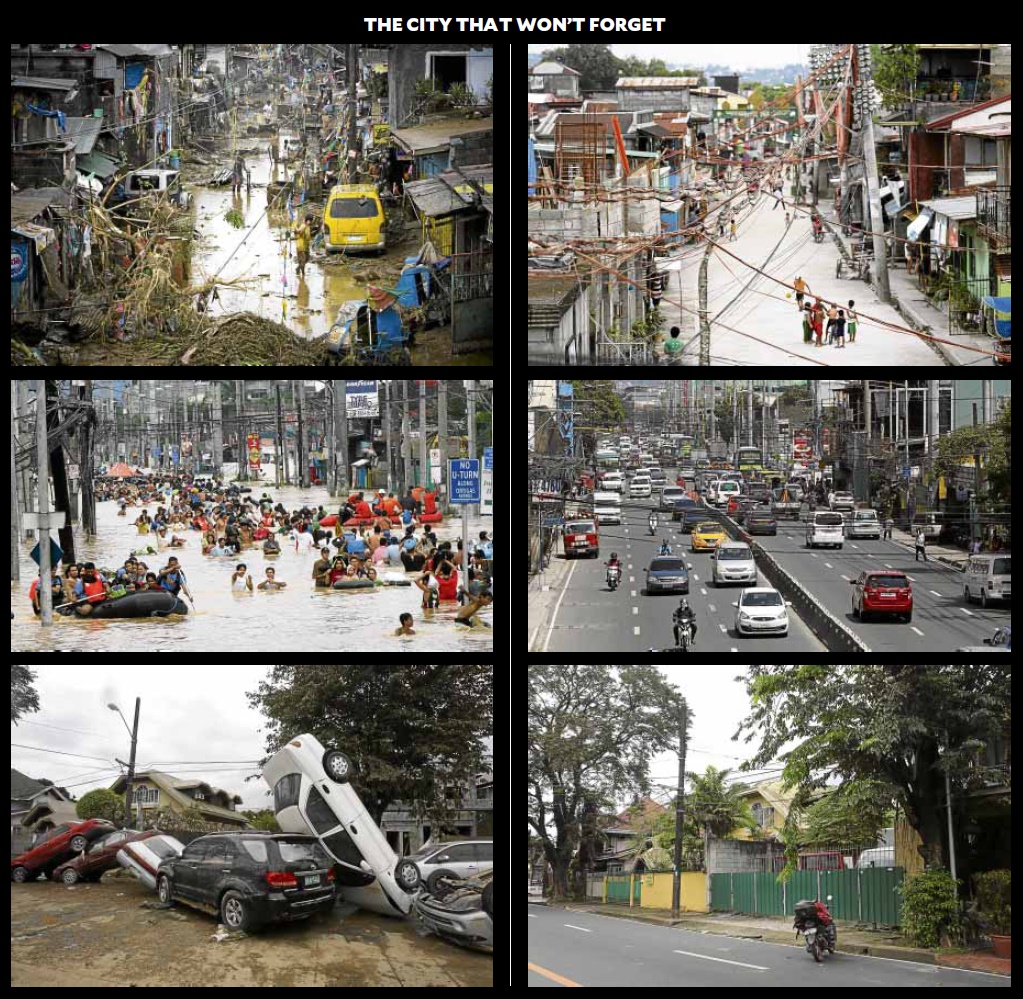

Today is 10 years to the day Tropical Storm “Ondoy” (international name: Ketsana) unleashed a month’s worth of rainfall in just six calamitous hours, causing Marikina City’s eponymous river to rise to an unprecedented 23 meters above sea level.

Even now, a decade later, Papong, 38, struggles to find words to describe the disaster that upended his riverside neighborhood at Barangay Industrial Valley Complex (IVC). “The deluge was so severe, it took everything from us,” he says. “The only thing I still had afterwards were the hair on my head and the clothes on my back.”

Papong is now part of a group of volunteers known as “Bantay Ilog,” or The Guardians. In the event of another catastrophe, they will be among the first responders, charged with facilitating the prompt evacuation that was fatally lacking during Ondoy.

While it may seem strange for him to willingly spend his days watching the river that almost did him in, Papong says, he likely would not be a volunteer if not for the sense of community he found in the midst of the floods.

Residents stepping up

In the decade since Ondoy, Marikina’s local government has received the lion’s share of attention for the strides it has made in disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) efforts.

But city officials are quick to acknowledge that ordinary residents — those whose lives were devastated by the floods — have been just as crucial to Marikina’s steady recovery.

Ondoy may have changed certain neighborhoods in the city for good. But in its wake, scores of volunteers and leaders—bound by a shared trauma that has not receded as swiftly as the floods—have stepped up to take a central role in rebuilding.

A part of Metro Manila, Marikina sits on a valley bounded by the picturesque Sierra Madre mountain range and the rolling hills of Quezon City. Before it became synonymous to floods, it was mostly known for its shoemaking industry that had lifted it from being a sleepy town to an urbanized locale.

On Sept. 26, 2009, everything changed course. Within hours Ondoy dumped 341 millimeters of rainfall over Metro Manila and surrounding provinces, causing Marikina River to swell and overflow into densely populated neighborhoods near its banks, whether urban poor communities or affluent subdivisions.

Although they live in various parts of the city, residents nurse common memories: muddy waters quickly surging into their homes, the frantic flight to rooftops for safety, and the sight of floods sweeping away cars, buildings, even people.

With the destruction so severe, the national government declared a state of calamity in Metro Manila and 23 provinces as the death toll rose to more than 700 people.

“I guess the terms we could use to describe what we felt then are ‘shock and awe,’” says Dave David, chief of Marikina City’s DRRM office.

No such office or position existed at that time. In fact, it was Ondoy that ushered in its creation under Republic Act No. 10121, or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act passed in 2010.

Integral partnership

But even without a DRRM office then, David says, Marikina already had a valuable resource: Rescue 161, which provided for emergency response in the city in 1993. Still, it did not prove enough, as the local government itself, along with its residents, had never experienced such a disaster.

“Before Ondoy came, our systems that we use were already in place. But the problem with that incident was nobody—I mean, nobody—was expecting that magnitude,” David admits.

The hard lessons from the 2009 storm are now the bedrock of the local government’s approach to disaster preparedness and response, one that goes beyond merely dictating what residents should do if and when an Ondoy-like calamity happens again.

“The secret in our resiliency is the partnership between the city government and the community. No matter how [much] resources the city has, it will never be enough if the community will not respond,” David says, adding:

“Nothing will happen in any of the government’s programs in disaster preparedness or risk reduction [without] community participation.”

These programs are no longer merely reliant on the barangay, which could encompass thousands of families. Instead, the DRRM office has gone smaller: reaching communities and volunteer groups, whether small neighborhoods, homeowner associations, or interest groups such as religious organizations and even motorcycle clubs.

The training involves necessary skills that would benefit residents beyond typhoons, including basic life support, first aid and basic water rescue, following a module that emphasizes community action for disaster resilience and response.

Residents are also made aware of what David calls “ever changing” protocols when it comes to disaster response, which are modified based on the most recent disaster scenario.

“Because of the lessons learned from Ondoy, the [residents’] awareness levels are much higher… What we share with them is experiential, not conceptual or theoretical,” he says.

Rising to the challenge

Yet even without training from the city government, many residents have embraced the challenge of leading their community to prepare for disasters, partly driven by their own experiences during Ondoy and even up to this day.

For Teresa Bernardo, Ondoy provided the motivation to take greater responsibility not only for her family but also for her neighborhood in flood-prone Tumana.

In 2009, she experienced what it was like to be helpless amid a disaster, watching in fear as Marikina River swelled and devoured her three-story home.

Ten years later, as a member of an active group of volunteer women in her barangay, Bernardo sees herself as a leader. Once the river waters rise to an alarming level, she transforms into a mother looking out for at least 100 households, knocking on doors to warn the occupants to prepare for evacuation.

That action is complemented by a tool that was not yet as accessible when Ondoy hit in 2009: technology and social media. When going house to house proves too tedious for Bernardo, she sends a quick snap of the swelling river to various members of a group chat over a messaging app.

Before Ondoy struck, Papong hadn’t considered himself much of a volunteer either. But the waters rose so quickly in his area that he was jolted by a need to act despite, apart from an older brother he lived with, not having a family of his own then.

He helped evacuate families to safer areas and carried children to higher floors. He kept on even when his slippers fell apart and his bare feet began to ache. When the floods subsided, he assisted neighbors in the grueling work of clearing their homes of trash and mud.

Elmer Corales, a Barangay IVC kagawad (councilor), pushed a resolution last year to officially absorb Bantay Ilog volunteers into the village, providing a newfound legitimacy. Now, they receive small incentives for their crucial work.

Constant fear

Corales says the Bantay Ilog volunteers are a “low tech” version of the city’s Rescue 161, but the operation is grounded on “community spirit.”

Aside from monitoring the water level, the volunteers guard against those who throw trash into the river or linger smoking on its banks. They send home loitering kids and sweep sidewalks. Thanks to the rich soil on the banks, they tend to a small garden of sweet potato leaves and saluyot.

“It’s the volunteerism that’s at the heart of what this group does,” Corales says.

Yet it is impossible to discount that the volunteer spirit sprang from an undercurrent of fear that they may see a reprise of their bitter experience in 2009.

“That fear never leaves,” says Libby Dipon, another kagawad of Barangay IVC. She says there are still nights when heavy rain keeps her awake, agitated by a need for vigilance that Ondoy had stirred.

Officials and residents alike say that since Ondoy, countless families have added a third floor to their houses as insurance. Anything of value, from personal belongings to home appliances, have been moved to higher floors.

And while a number of families moved away after 2009, many more have stayed in the same houses that were besieged by the torrent of mud and water.

Though the wrath of nature is often touted as the great equalizer, it remains a reality that the communities that suffered greatly under Ondoy, and in the years that followed, were the low-income communities living near the riverbanks.

“It’s simple: This is where our lot is,” Bernardo says. “It’s too costly to move elsewhere.”

Always on its feet

Ondoy has been called a “100-year flood,” but climate change whipping up sea levels and more extreme disasters leaves no opportunity for the city to be complacent, says Marikina Mayor Marcelino Teodoro.

To keep pace with rapid changes, efforts to beef up the city’s flood prevention structures are in a perpetual flux. According to City Engineer Ken Sueno, two trucks are deployed throughout the city daily to unclog drains, which are themselves subjected to constant system upgrades.

The local government is also engaged in an enduring effort to tame the city’s mighty river with a slew of projects to bolster slope protection, increase flood interceptors and deepen its carrying capacity through dredging and retention walls.

It’s as though the city keeps a chip on its shoulder after the shock of Ondoy, and, roused by a collective paranoia, has swung into hyperdrive to prevent a similar crisis. But the DRRM chief concedes that no strategy is foolproof.

“The highlight of our experience with Ondoy is that we can never be ready,” David says. “With the uncertainty of nature, nobody can claim they are ready, because we can never know the magnitude of what nature will give us.”

Mayor Teodoro airs a similar sentiment: “We are better prepared now. But we cannot be fully prepared.”

(To be continued)

Published: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1169714/ondoy-10-years-after-marikina-volunteers-rise-from-trauma